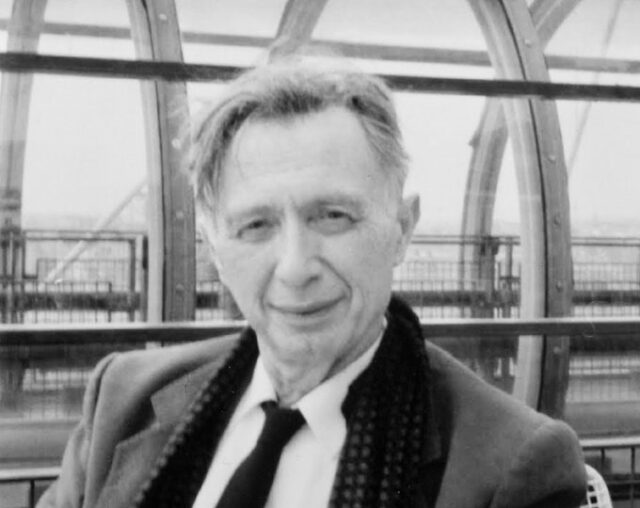

I stand before the universe a less embarrassed man today. For it appears that I am in good company among those temporarily fascinated, if not intellectually seduced, by the late Jacob Taubes. Having first gleaned he was an academic charlatan from comments made by Seth Benardete in his book-length interview, Encounters and Reflections, I stopped paying Taubes much mind over a decade ago. Not that there is much to mind. His dissertation, Occidental Eschatology, is the only book he published in his lifetime; a volume of fragments under the title From Cult to Culture is also available in English, as are his late-life lectures on St. Paul’s political theology. To his credit, Taubes had interesting things to say on a variety of topics, though it appears that several them belonged to other people. He made enemies throughout academia during his lifetime, yet somehow managed to temporarily teach at some of the most prestigious schools in the world. Skilled in the art of self-promotion, Taubes got extraordinarily far while accomplishing very little, which is why he has long been ripe for biographical treatment in the form of Jerry Z. Muller’s Professor of Apocalypse: The Many Lives of Jacob Taubes (Princeton University Press 2022).

At first blush, it may seem strange that Muller dedicates over 600 pages to an intellectual who never bothered to pen nearly that much in his lifetime. Taubes’s few ideas, cobbled together as they were from the superior works of thinkers such as Karl Lowith, Hans Jonas, and Gershom Scholem, probably don’t deserve extensive treatment, but Muller gives them all a sympathetic read while never losing sight of where Taubes lifted them from. Muller also spends a great deal of time examining Taubes’s bountiful shortcomings as a human being. A notorious philanderer who had no problem spreading vicious gossip while stabbing his modest circle of friends in the back, one of the most puzzling aspects of Taubes’s career is how relatively successful it was despite his destructive behavior. As Scholem observed, Taubes lacked both academic and moral self-discipline, yet he somehow managed to draw devoted students up until his death in 1987. Muller’s book provides ample material for those interested in unlocking this mystery.

It is probably not possible for someone like Taubes to exist today. The dictate to “publish or perish” is substantially stronger today than it was half-a-century ago. With the advent of social media and electronic databases, it is relatively easy to pin down plagiarism and unmask phonies. What Taubes had going for him, namely an encyclopedic recall of variegated subjects across disciplines, is less impactful today than it once was. Were Taubes operating at the height of his powers in 2022, he would make for a fun person to follow at Twitter and have around at parties to stir the pot, but probably not much else. As for his atrocious reputation for womanizing and betrayal, no doubt Taubes would be ripe for cancellation in the contemporary world.

At the same time, there are still lessons to be drawn from Taubes’s life. It remains disturbingly easy for self-professed intellectuals, regardless of ideological stripes, to present themselves as radically more than they are. Jordan Peterson comes to mind. So, too, does Rod Dreher. On the lower-rungs of the success ladder rest any number of online Catholic grifters, and among the left, the op-ed pages of the New York Times and Washington Post are flooded with pop analysts whose hyperbolic ravings about the “end of democracy” and a well-orchestrated (as opposed to painfully inept and embarrassing) conservative conspiracy to rid every one of their rights pass for critical commentary. Few of these folks ever achieve great success in academic, but why bother when clicks, re-tweets, podcasts, and books bound for the bargain bin can keep one plied with white wine and oysters until the cows come home. Certainly Jacob Taubes could appreciate that.