Note: I will return to my series on on defending debt collection lawsuits shortly. I am going to mix them in with some thoughts on Eric Voegelin’s under-appreciated lecture, “Clericalism.”

Tucked away in the rear of the first volume of his collected correspondence lies Eric Voegelin’s 1946 lecture, “Clericalism.” Delivered after the close of the Second World War, this short talk, like many of Voegelin’s writings at the time, foreshadow his turn from chronicling the history of political ideas to developing a philosophy of consciousness, particularly in the final two volumes of his massive Order and History. Although Voegelin’s Christianity, to the extent that he was a Christian, could hardly be called “orthodox” by either Catholic or his native Lutheran lights, there is no doubt that he took Christianity seriously and was committed to the Christian intellectual tradition, often in an Augustinian key. Voegelin had also drunk deeply from the well of Aquinas, though there is scant evidence that he ever held Catholic neo-Thomism any closer than arm’s length. He expressed at points admiration for certain papal statements, but they carried no doctrinal weight for him; they could be criticized freely. Before saying more about Voegelin’s lecture, it is important to highlight what Voegelin means by “Christianity.”

Christianity is not a system of social ethics, but a religion. It is a faith concerned with the destiny of the soul; and this faith as such has no direct bearing on the formation of the social environment; it can have a bearing only indirectly insofar as the conduct required of the Christian is not compatible with the exigencies of every social order. Hence the Church cannot develop a positive social program; it can only deal with concrete social questions as they arise, and try, by counsel, to guide the conduct of individuals in such a manner that it will become Christian conduct.

When Voegelin speaks of “the Church,” he almost always has in mind the Roman Catholic Church, even when he touches on Protestant thinkers. Some, particularly contemporary integralists, may take umbrage with Voegelin’s dismissive attitude toward the Church “develop[ing] a positive social program” rather than “deal[ing] with concrete social questions as they arise.” That is fair, though throughout “Clericalism,” and indeed against the European backdrop that intellectually formed Voegelin, he witnessed the pitfalls of Catholics aligning with this-or-that political movement to resist what can broadly be called the de-Christianization of society. To the extent the Church ever articulated something like a social program, it came to the table too late. Revolutionary and counter-revolutionary forces were already at work; all the Church could do was react, and sometimes react poorly.

By way of illustration, Voegelin casts a glance toward Pope Leo XIII’s landmark encyclical Rerum Novarum (RN). His initial assessment is rather positive: “The Encyclical is in many respects a laudable document, particularly in its analysis of the ideology of class war, but it fails in the crucial point, that is in the discussion of private property. It restates the position of the Church with regard to the justness and necessity of private property for the building of an integral human existence, and insofar it is on safe ground.” What’s so bad about that? Voegelin continues:

The ground becomes less safe, however, when the Encyclical proceeds to berate Marxism flatly for demanding the abolition of private property, without entering into the distinction between property of objects of consumption and long-range personal use on the one side, and property in the instruments of large-scale industrial production on the other side. …[W]e might at least expect of the Papal counsellors that they would offer a more palatable substitute of their own for the condemned solution. But what do we find instead? A concentration of the argument on the property in land. The idea of a Communist society is against natural law because it deprives the individual of the possibility to own his piece of land as the basis of his personal existence. Under a Communist society the industrial worker would not be able to invest his savings in land. Well, our attitudes towards the merits of a Communist society may differ, but, I think, we can all agree that it is not the primary sorrow of the industrial worker in our society to invest his savings in landed property and that a few other factors determine the drive towards a nationalization of industries and planned economy. The later Encyclicals, in particular the Quadragesimo Anno of 1931, have become more cautious in their formulations, but the position is not yet surrendered in principle. The Church is still today seriously handicapped in dealing with the burning problems of industrial society by what we may call its rural hangover.

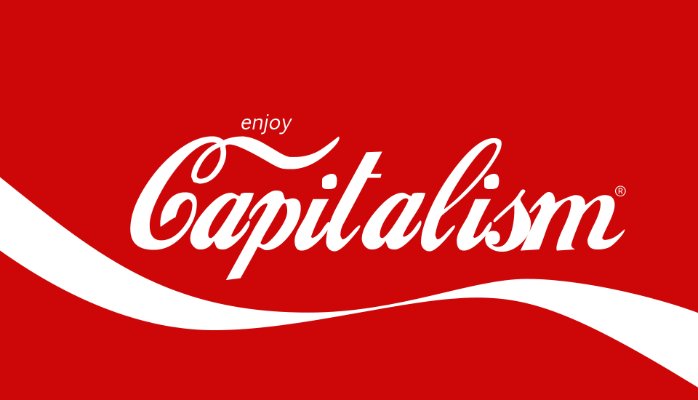

The “burning problems of industrial society” continued to rage for most of the 20th century with the Church sending what Voegelin would likely call “mixed messages” about how not just Catholics, but all peoples, ought to relate to it. While I have never been shy about arguing that there is a consistent anti-capitalist thread running from RN to the social pronouncements of Pope Francis, the fact that well-funded organizations such as the Acton Institute can take the Church’s social magisterium and tilt it toward pro-market ideology may be a sign of the incomplete, reactive, and somewhat ambiguous nature of that teaching. A certain romanticism, the Church’s “rural hangover,” pointed to a concrete economic situation beyond capitalism because it consciously pointed backwards. After the 1960s, the Church purported to be more “forward facing,” though it seems Voegelin is correct that no comprehensive social program has emerged and there remains more questions than answers lurking about.

Catholics who take RN and the pre-Vatican II social magisterium seriously are few and far between. Even traditional Catholics, those purported champions of authenticity in Catholic doctrine, are routinely lured to embrace market-economy ideology under the guise of “freedom” (or, worse, “rights”). Pockets of “back to the land” Catholics, those eccentric few, still exist; God bless them. However, to say they exert any meaningful influence on contemporary Catholic thought stretches credulity. Although the decades just before and after World War II revealed examples of “Catholic Action” whereby the laity, with the direct or indirect guidance of the clergy, tried to develop on-the-ground responses to industrial society, they too have faded out of history. And now that we have arrived at, or are rather drowning in, post-industrial society, what is to be done?

To listen to Pope Francis, something akin to a socialist solution, understood broadly, may be required, though that is not a popular solution by any stretch of the imagination. Whether Francis and the curia understands the state of the world economy is an open question. What appears evident, though, is that the Sovereign Pontiff understands deeply that something is terribly wrong with it and no amount of misguided faith in the “Invisible Hand” is going to correct it. Integralists may have once had something valuable to add to the conversation if they hadn’t become preoccupied with genuflecting before the altar of raw power while developing their own brand of “QAnon Catholicism.” By casting so many aspersions on Marxism over a century ago, the Church, particularly Francis, will struggle mightily to suggest a socialist solution that can in any sense be called “Catholic.”

There is more to say on Voegelin’s “Clericalism,” but I will leave it there for now. By the close of the lecture, Voegelin expressed enthusiasm for the hope that certain thinkers would keep the light of Christianity burning. They were “the future” and on that score, he was correct. Of course, Voegelin had no idea what that future would look like in 1946.