Many sophisticated arguments have been made for and against the application of the death penalty, most consequentialist and some deontological. In Catholic circles, debate over the death penalty recently heated up after Pope Francis condemned the practice outright. That pronouncement, like so many pronouncements of this Pontiff, appeared to conflict with the Church’s prior teaching on the matter, which recognizes the permissibility of the death penalty while allowing that there may be prudent reasons for civil authorities to refrain from using it. In the United States, the death penalty is legal in 31 states, though four currently have a moratorium on the practice. This term, the Supreme Court of the United States will hear arguments about why the death penalty should be abolished under the Punishments Clause of the Eighth Amendment. That clause, rightly or wrongly, has come to be interpreted in line with our “evolving standards of decency,” an elastic measuring stick that I, as a tender (and naïve) youth of 27, criticized in my first foray into legal scholarship as historicist.

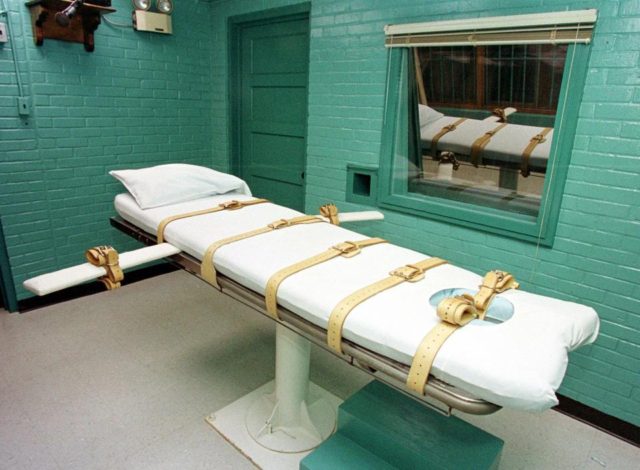

Last night, the state of Alabama attempted to put to death Doyle Lee Hamm for the murder of a motel clerk in 1987. Hamm, who has cancer, is at risk for his execution by lethal injection to go awry because of the damage to his veins. In short, there is a high risk that Hamm’s veins will rupture during the execution procedure, sending lethal chemicals into his flesh and leading to a protracted, torturous death.

Despite numerous petitions on his behalf, the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals determined, based on affidavits submitted by Alabama, that the execution could still proceed so long as certain procedures were in place, including using veins in Hamm’s lower extremities rather than his arms. In a last ditch effort to save Hamm from a potentially excruciating execution, his attorney, Columbia law professor Bernard Harcourt, appealed to the Supreme Court to review the 11th Circuit’s ruling. After granting a brief stay, the Court voted 6-3 to deny cert, thus paving the way for Alabama to carry out the execution. For 2 1/2 hours, Alabama officials attempted to find veins on Hamm capable of receiving the lethal injection; they could not. And so, less than half-an-hour before the death warrant was set to expire, the execution was called off.

What went on during those 2 1/2 hours remains a mystery. Only Hamm and those officials and correctional officers present know for sure. Hamm’s attorneys, family, and the media were not present, which is why an emergency motion was filed and granted today in federal district court. According to the order, Hamm is supposed to receive a full medical evaluation tomorrow with an official hearing on Monday which, inter alia, will allow those present, including Hamm, to give an official accounting of last night’s events. The district court has also ordered that no evidence from the aborted execution is to be disposed of, including Hamm’s clothing. What the examination, hearing, and physical evidence will reveal is anyone’s guess, though there is a high likelihood that Hamm was stuck repeatedly with a needle for more than two hours before the debacle was called off.

Distressingly, Hamm’s case received scant mainstream media attention until the execution was almost underway. The Washington Post started covering the matter late last night, noting that the Supreme Court had rescinded its stay and highlighting the risks involved with executing a cancer-stricken man. Aside from a handful of Catholic commentators and outlets that stand firmly against the death penalty in all circumstances, those “enlightened young Catholics” who routinely stock up their moral capital by chasing after causes they think will win them credibility among mainstream Leftists were silent. Why? Perhaps because Hamm, a man who far too many in America would deride as “poor white trash,” wasn’t “hip” enough to care about. Similarly, the most unsettling aspect of Hamm’s case, namely the years of legal malfeasance that have kept him on death row, isn’t “shocking” or “immediate” enough to generate Facebook “Likes” and re-Tweets. Or maybe, just maybe, the routine injustices attendant to America’s penal culture is an acceptable byproduct of a larger system of policing and surveillance meant to secure the essential promise of liberalism, the essential promise that so many “illiberal Catholics” refuse to let go of, namely an unserious life of entertainment, etc.